My Migration Story

“…and that’s how a bunch of Asians ended up in Kansas,” is how I’ve ended many an explanation of my family’s roadmap and heritage.

My dad was born in Mainland China in 1951, post-World War II, shortly after Mao Zedong became chairman. The Communist Party had taken power and the Nationalists had fled to Taiwan. This was a turning point in history, and for people like my dad’s parents, it was finally time for the impoverished and working class to ascend in rank and influence. My grandpa had been nine years old when the Japanese invaded China, killing his parents and making orphans of many. It was as a youth that he—and my grandma and many like them—became indoctrinated into the Communist military. They were ready and eager to be at the forefront of a new, progressive China.

Meanwhile, the world changed in a very different way for my mom’s family in Taiwan. Taiwan had lived under Japanese rule from 1895 to 1945, a 50-year span before returning to China after the war. People like my paternal grandpa grew up with a Japanese education, singing patriotic Japanese songs. His family had lived well under the Japanese. All of this changed overnight. My mom’s family lost their property to the Chinese government, and at the age of 16, my grandpa left school to go to work to support his nine younger siblings and family.

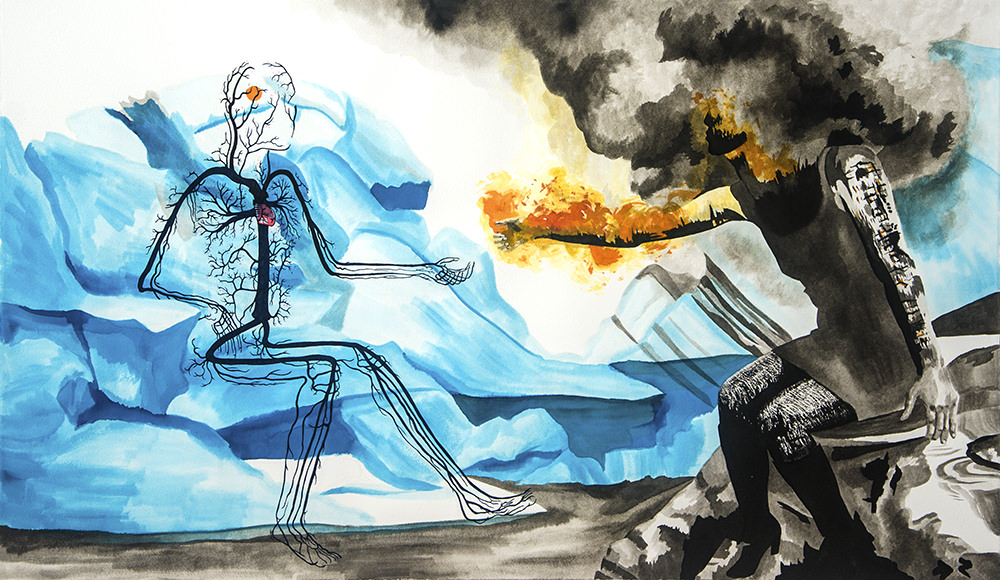

This might be a story from the East, but the premise doesn’t get more Montague and Capulet than this. There’s a lot of friction between China and Taiwan and volumes of history that I won’t get into here. The truth of the matter is that both sides of my family’s story are nothing short of incredible, devastating, traumatic, and fiercely resilient against all odds. They are also eerily reminiscent of what we see in politics today, left vs right, liberal vs conservative, and, always, poor vs poor, even when those in power have ascended from the disadvantaged class.

Moving on, how did my family end up in the US? Again, in opposite ways. My dad endured many interruptions in his life, from the Great Famine that followed Mao’s failed Great Leap Forward to the Cultural Revolution that shut down all schools and effectively ended his generation’s education. And yet in spite of not having much schooling, in spite of joining the military to avoid exile to the countryside, in spite of seeming destined to stay forever as a factory worker, my dad found his name on a special list while working at a TV factory. China had an education gap, and to get more students into the universities, the factories were holding a vote. Five employees would get the chance to pursue an education based on peer votes. My dad was one of those five, and he received the chance to study English at the Beijing Language Institute. During his years at the institute, China reopened to the West, and my dad became one of the first people to get a Visa to study in the United States. He was the only member of his family to immigrate here.

My mom, conversely, already had family living in the States. Her uncle invited my grandparents and their four children to come help with the family restaurant in Connecticut. It so happened that the year they moved to Connecticut, my dad was working at the family’s restaurant. He and my mom started dating shortly after meeting, and married two years later. It was by then that my mom decided to move to Kansas City, to be closer to family living in the Midwest.

Four years later, in 1988, my parents opened their own Chinese takeout restaurant, the same year that I was born. From that day forward, my parents never failed to remind me (maybe a little excessively) of just how lucky I am. Lucky that they survived enough crap for me to have a chance of existing. Lucky that they scrounged together enough savings to stop working at other people’s restaurants and open their own, to earn enough to raise a kid. Lucky, as a girl, to have been born on US soil. Lucky to speak English natively in a world that favors it, for education and business and success.

So it comes as no surprise that I’ve always understood how immigration was about possibilities, and the “American dream” about beating the odds. The union of my parents’ stories couldn’t have happened anywhere but here in the US. It’s a bit of a funny plot-twist. A Chinese-Communist and a Taiwanese-Nationalist would have had a slim-to-none chance of meeting or ever marrying. Even here in this land of immigrants, we forget that interracial marriage was illegal until 1967, and yet had the law not changed, in the States, my parents would still be seen as the same race, and completely invisible in their political divides. Perhaps even more than possibilities, the United States, with its identity built on the shoulders of migrants, is a place where we are meant to resolve differences.

That may be the biggest lesson to take from this story, for now. The problems we have here aren’t new. Immigration isn’t new, not for humans, not for any living species. As we move away from our cultural roots, we find ourselves instead carrying with us the troubles of social, racial, sexual, and religious inequities. And perhaps we have done so, for a greater chance than anyone before us to encounter and therefore resolve our differences.

How do we do that? Right now, we have a bad habit of creating blanket terms and stereotypes that oversimplify people and complicate circumstances. “Asian-American” lumps together literally billions of people of diverse backgrounds—Chinese, Japanese, Thai, Hmong, Vietnamese—to name a few. “White” means European descent and “black” means African descent, regardless of whether your parents are from Ireland or Greece, Kenya or Jamaica, or four generations from Arkansas. To be Hispanic means you must be brown, even though Latin American countries are as varied in race and color and immigration patterns as their North American counterparts. In our ironic human nature, this homogeny of race and culture is exactly what ends up dividing us by the social status of color, by the patriotism of Us versus Them. When we forget our history, we lose our connections to the rest of humanity.

What, then, does sharing my migration story mean to me? It means keeping the culture and the history as a part of my education, and sharing something that others of any background might identify with. It means encouraging people to keep their stories alive, because it’s through stories that we find our common ground. It means understanding that animals and plants have always migrated in the quest for resources, diversification, and a better life. Our willingness to diversify has always driven progress. It only makes sense that our love of diversity will strengthen our unity.

Jenie Gao’s TEDx Talk in 2016.

You must be logged in to post a comment.